By Joby Warrick, The Washington Post

CUBA, N.M. — The methane that leaks from 40,000 gas wells near this desert trading post may be colorless and odorless, but it’s not invisible. It can be seen from space.

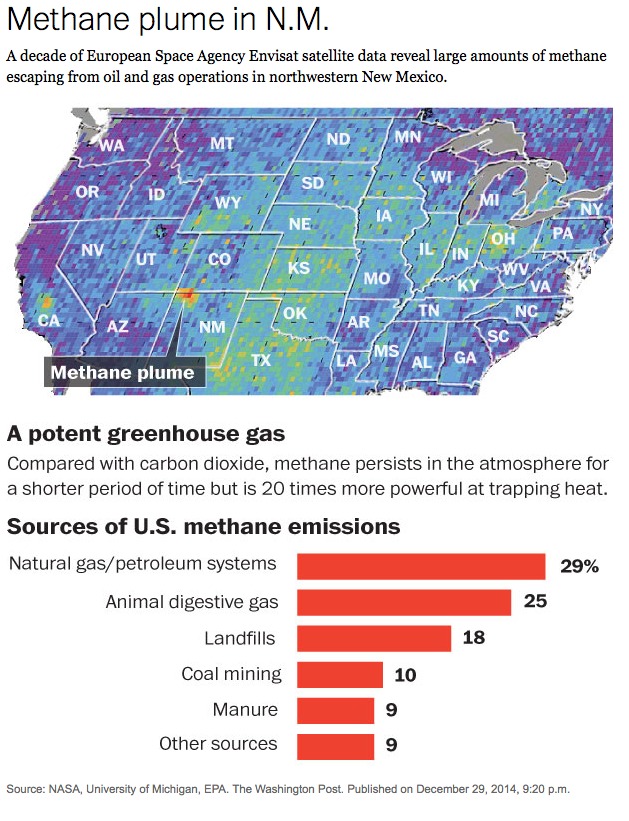

Satellites that sweep over energy-rich northern New Mexico can spot the gas as it escapes from drilling rigs, compressors and miles of pipeline snaking across the badlands. In the air it forms a giant plume: a permanent, Delaware-sized methane cloud, so vast that scientists questioned their own data when they first studied it three years ago. “We couldn’t be sure that the signal was real,” said NASA researcher Christian Frankenberg.

The country’s biggest methane “hot spot,” verified by NASA and University of Michigan scientists in October, is only the most dramatic example of what scientists describe as a $2 billion leak problem: the loss of methane from energy production sites across the country. When oil, gas or coal are taken from the ground, a little methane — the main ingredient in natural gas — often escapes along with it, drifting into the atmosphere, where it contributes to the warming of the Earth.

Methane accounts for about 9 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, and the biggest single source of it — nearly 30 percent — is the oil and gas industry, government figures show. All told, oil and gas producers lose 8 million metric tons of methane a year, enough to provide power to every household in the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia.

As early as next month, the Obama administration will announce new measures to shrink New Mexico’s methane cloud while cracking down nationally on a phenomenon that officials say erodes tax revenue and contributes to climate change. The details are not publicly known, but already a fight is shaping up between the White House and industry supporters in Congress over how intrusive the restrictions will be.

Republican leaders who will take control of the Senate next month have vowed to block measures that they say could throttle domestic energy production at a time when plummeting oil prices are cutting deeply into company profits. Industry officials say they have a strong financial incentive to curb leaks, and companies are moving rapidly to upgrade their equipment.

But environmentalists say relatively modest government restrictions on gas leaks could reap substantial rewards for taxpayers and the planet. Because methane is such a powerful greenhouse gas — with up to 80 times as much heat-trapping potency per pound as carbon dioxide over the short term — the leaks must be controlled if the United States is to have any chance of meeting its goals for cutting the emissions responsible for climate change, said David Doniger, who heads the climate policy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group.

“This is the most significant, most cost-effective thing the administration can do to tackle climate change pollution that it hasn’t already committed to do,” Doniger said.

Methane’s hot spot

The epicenter of New Mexico’s methane hot spot is a stretch of desert southeast of Farmington, N.M., in a hydrocarbon-soaked region known as the San Juan Basin. The land was once home to a flourishing civilization of ancient Pueblo Indians, who left behind ruins of temples and trading centers built more than 1,000 years ago. In modern times, people have been drawn to the area by vast deposits of uranium, oil, coal and natural gas.

Energy companies have been racing to snatch up new oil leases here since the start of the shale-oil boom in recent years. But long before that, the basin was known as one of the country’s most productive regions for natural gas.

The methane-rich gas is trapped in underground formations that often also contain deposits of oil or coal. Energy companies extract it by drilling wells through rock and coal and collecting the gas in tanks at the surface. The gas is transported by pipeline or truck to other facilities for processing.

But much of this gas never makes it to the market. Companies that are seeking only oil will sometimes burn off or “flare” methane gas rather than collect it. In some cases, methane is allowed to escape or “vent” into the atmosphere, or it simply seeps inadvertently from leaky pipes and scores of small processing stations linked by a spider’s web of narrow dirt roads crisscrossing the desert.

For local environmental groups, gas-flaring is a tangible reminder of the downsides of an industry that provides tens of millions of dollars to local economies as well as to federal tax coffers. Bruce Gordon, a private pilot and president of EcoFlight, an environmental group that monitors energy development on federally owned land, recently banked his single-engine Cessna over a large oil well near Lybrook, N.M. He pointed out two towers of orange flame where methane was being burned off, a practice that prevents a dangerous buildup of pressure on drilling equipment but that also wastes vast quantities of methane.

“For these companies, the gas is worthless — the oil is what they want,” Gordon said. The burning converts methane into carbon dioxide — another greenhouse gas — while contributing to the brown haze that sometimes blankets the region on sunny days, he said.

Other environmental groups have documented leaks of normally invisible methane using infrared cameras that can detect plumes of gas billowing from wells, storage tanks and compressors. All of it contributes to the giant plume “seen” by satellites over northwestern New Mexico, a gas cloud that NASA scientists say represents nearly 600,000 metric tons of wasted methane annually, or roughly enough to supply the residential energy needs of a city the size of San Francisco.

The NASA analysis estimated the average extent of the gas plume over the past decade at 2,500 square miles — and that was before the recent energy boom from shale oil and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, said Frankenberg, the NASA scientist.

Possible remedies

But spotting the leaks is far easier than fixing them. The Obama administration is reviewing a host of possible remedies that range from voluntary inducements to more costly regulations requiring oil and gas companies to install monitoring equipment and take steps to control the loss of methane at each point in the production process. The announcement of the administration’s new policies has been repeatedly delayed amid what officials describe as internal debate over the cost of competing proposals and, indeed, over whether methane should be regulated separately from the mix of other gases given off as byproducts of oil and gas drilling.

The American Petroleum Institute, the largest trade association for the oil and gas industry, contends that companies are already making progress in slashing methane waste, installing updated equipment that reduces leaks. New regulations are unnecessary and would ultimately make it harder for U.S. companies to compete, said Erik Milito, API’s director of upstream and industry operations.

“Every company is strongly incentivized to capture methane and bring it to the market,” Milito said. “We don’t need regulation to tell us to do that.”

But environmentalists point to problems with old pipelines and outdated equipment that are the source of more than 90 percent of the wasted methane, according to a report earlier this month by a consortium of five environmental organizations. The study said relatively modest curbs would result in a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions over two decades comparable to closing down 90 coal-fired power plants.

The report’s authors noted that the measures would also help protect taxpayers who, after all, are the ultimate owners of the oil and gas taken from federally owned lands, including most of New Mexico’s San Juan Basin.

“The good news is that there are simple technologies and practices that the oil and gas industry can use to substantially reduce this waste,” said Mark Brownstein, an associate vice president for climate and energy at the Environmental Defense Fund, one of the contributors to the report.

“You don’t have to be an environmentalist to know that methane leaks are simply a waste of a valuable national energy resource,” he said.

![A grove of affected aspens in the La Sal Mountains. Stands along the roads to Geyser Pass and Oohwah Lake, and along the east side of the range on the flanks of South Mountain, have been particularly hard hit by leaf blight. [Photo courtesy of Brian Murdock / U.S. Forest Service]](https://i0.wp.com/deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2015/09/Aspens02-300x167.jpg?resize=300%2C167)